When the object now called SN 1006 first appeared on May 1, 1006 A.D., it was far brighter than Venus and visible during the daytime for weeks. Astronomers in China, Japan, Europe, and the Arab world all documented this spectacular sight, which was later understood to have been a supernova. With the advent of the Space Age in the 1960s, scientists were able to launch instruments and detectors above Earth's atmosphere to observe the Universe in wavelengths that are blocked from the ground, including X-rays. The remains of SN 1006 was one of the faintest X-ray sources detected by the first generation of X-ray satellites.

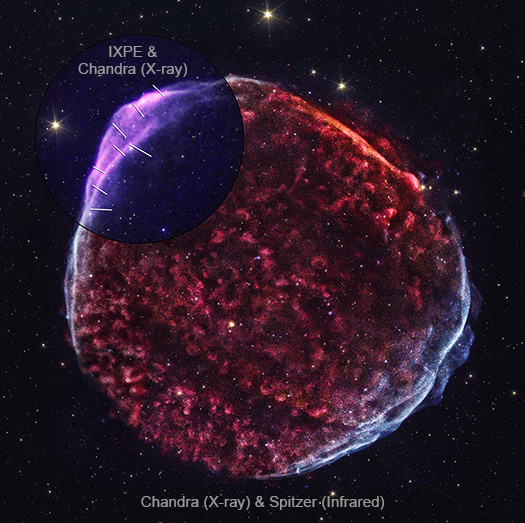

This new image shows SN 1006 from two of NASA’s current X-ray telescopes, the Chandra X-ray Observatory and Imaging X-ray Polarimetry Explorer (IXPE). In the full image of SN 1006, red, green, and blue show low-, medium-, and high-energy detected by Chandra. The IXPE data, which measure the polarization of the X-ray light, have been added in the upper left corner of the remnant in purple. The lines in that corner represent the direction of the magnetic field.

Prior to this result, X-ray observations of SN 1006 offered important evidence that supernova remnants can radically accelerate electrons, making them a major source of highly-energetic cosmic rays detected on Earth. Chandra observations of SN 1006 previously suggested that the magnetic field in the sharp edges of the supernova remnant in the upper left and lower right is almost ten times stronger than surrounding regions. This enhances the acceleration of particles to high energies.

IXPE’s new findings helped validate and clarify theories that SN 1006’s unique structure is tied to the orientation of its magnetic field, and that the supernova blast waves correspond most closely with those field lines along its upper left and lower right edges, more efficiently sending high-energy particles streaming in those directions.

Researchers say the results demonstrate a connection between the magnetic fields and the remnant’s high-energy particle outflow. The magnetic fields in SN 1006’s shell are somewhat disorganized, per IXPE’s findings, yet still have a preferred orientation. As the shock wave from the original explosion goes through the surrounding gas, the magnetic fields become aligned with the shock wave’s motion. Charged particles are trapped by the magnetic fields around the original point of the supernova blast, where they quickly receive bursts of acceleration. Those speeding high-energy particles, in turn, transfer energy to keep the magnetic fields strong and turbulent.

A paper describing these results, publishing October 27, 2023 in The Astrophysical Journal, is available at https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.01879

IXPE is a collaboration between NASA and the Italian Space Agency with partners and science collaborators in 12 countries. IXPE is led by NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. Ball Aerospace, headquartered in Broomfield, Colorado, manages spacecraft operations together with the University of Colorado's Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics in Boulder.

NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center manages the Chandra program. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory's Chandra X-ray Center controls science operations from Cambridge, Massachusetts, and flight operations from Burlington, Massachusetts.

This release features a labeled, composite image of the supernova remnant SN 1006, debris from an exploded star that resembles a mottled red ball of churning fire against a softer backdrop of stars. The turbulent supernova remnant appears to be encircled by a gauzy blue and white ring that is most prominent at our lower right and upper left. This structure is markedly different from other rounded supernova remnants.

At the upper lefthand corner of this composite image, a labeled section of SN 1006 is highlighted in a blue-tinted circle. Within this circle, only the outer ring of the supernova remnant is shown, not the mottled red stellar material churning inside. This ring is part of the supernova’s expanding blast wave, which has been observed in X-ray light by both Chandra and the Imaging X-ray Polarimetry Explorer (IXPE). The soft backdrop of stars was captured in infrared light by the Spitzer Space Telescope.

Scientists are using these observations to map the magnetic field structures of SN 1006. They have surmised that this supernova remnant’s structure is tied to the orientation of its magnetic fields. Scientists theorize that the blast waves from the initial explosion correspond most closely with the magnetic field lines along its upper left and lower right edges. This correspondence results in particles being efficiently accelerated to high speeds.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||