Groups & Clusters of Galaxies

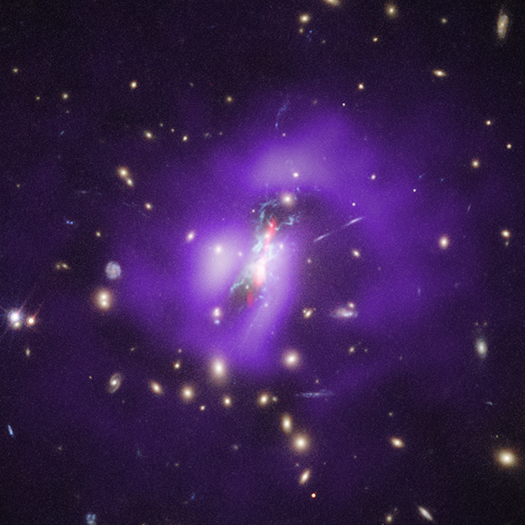

Bending the Bridge Between Two Galaxy Clusters

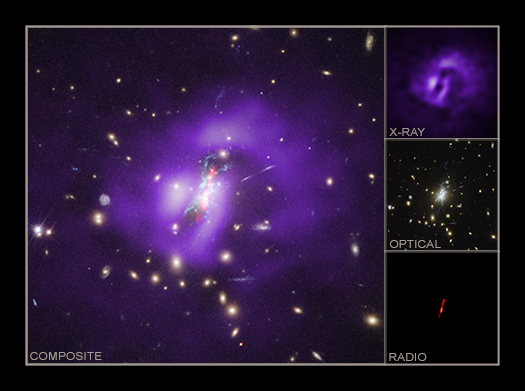

Abell 2384

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO/V.Parekh, et al. & ESA/XMM-Newton; Radio: NCRA/GMRT

Several hundred million years ago, two galaxy clusters collided and then passed through each other. This mighty event released a flood of hot gas from each galaxy cluster that formed an unusual bridge between the two objects. This bridge is now being pummeled by particles driven away from a supermassive black hole.

Galaxy clusters are the largest objects in the universe held together by gravity. They contain hundreds or thousands of galaxies, vast amounts of multi-million-degree gas that glow in X-rays, and enormous reservoirs of unseen dark matter.

A Very Mysterious Direction in the Universe

Konstantinos (Kostas) Migkas

We are pleased to welcome Konstantinos (Kostas) Migkas as a guest blogger. Kostas is a doctoral researcher in the Argelander Institute of Astronomy of the University of Bonn, Germany, and led the study that is the subject of our latest press release. He received his Bachelor's degree in Physics from the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece, in 2015. Then he moved to Germany and Bonn to obtain his Master's degree in Astrophysics in 2017. He started his PhD by the end of the same year in the group of Prof. Thomas Reiprich working on cosmology with galaxy clusters, exploiting a novel method they designed to study one of the key principles of cosmology.

Our understanding of the Universe has significantly improved in the last 25 years. The accelerating expansion of the Universe, the detailed observation of the leftover relic radiation from the Big Bang (cosmic microwave background, or CMB), the in-depth study of the Universe's structure and the unfolding of the cosmos in the whole range of the electromagnetic spectrum are some of the accomplishments that led astronomers to precisely constrain the so-called cosmological parameters. The latter describe the properties of the Universe in various ways. These include: how much "normal" and "dark" matter the Universe contains, the nature of the mysterious dark energy, and maybe most importantly, the expansion rate of the Universe.

To push cosmological knowledge forward, scientists have to inevitably make some assumptions about the Universe. One of the most fundamental ones is that it acts the same way towards every direction of the sky. Practically, this means that the behavior of the astrophysical objects, for instance galaxies or clusters of galaxies, should look the same no matter where we look. It also means that the cosmological parameters, including the expansion rate of the Universe, must be the same independent of the direction. We call this property "isotropy".

How To Do Particle Physics With Chandra

We are pleased to welcome Chris Reynolds as our guest blogger. Chris is a professor in the Institute of Astronomy at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, and led the study that is the subject of our latest press release. He received his Bachelors degree in Physics and Theoretical Physics from the University of Cambridge in 1992, and continued in Cambridge to graduate with his PhD in astronomy in 1996. He then moved to the University of Colorado Boulder for five years as a post-doctoral fellow and Hubble Fellow, before joining the faculty of the University of Maryland's Department of Astronomy. In 2017, after 16 years as a professor at the University of Maryland, he was lured back to Cambridge to take up the position of Plumian Professor of Astronomy and Experimental Philosophy. Chris is a high-energy astrophysicist who mainly works on the properties of supermassive black holes, although he has taken a detour into particle physics with his latest work, which is the subject of this blog post.

A little over 200 million light years from us lies the Perseus cluster, a swarm of a thousand galaxies trapped within the space of just a couple of million light years by the gravitational field of a massive ball of dark matter. This gravitational field doesn't just confine the galaxies. It also holds onto an atmosphere of hot (40-60 million Kelvin) gas that fills the space between the galaxies; this matter is known as the “intracluster” medium. At the center of all of this lies the unusual galaxy NGC1275, and at the center of this galaxy is a supermassive black hole that is driving powerful jets out into the intracluster medium. When my team observed the active galactic nucleus (AGN) in NGC1275 with the Chandra X-ray Observatory in late 2017, we thought that our focus would be the properties of this black hole and how it interacted with its surroundings. Little did we know that we'd be publishing a paper on particle physics, setting the tightest limits to date on light axion-like particles with implications for string theory!

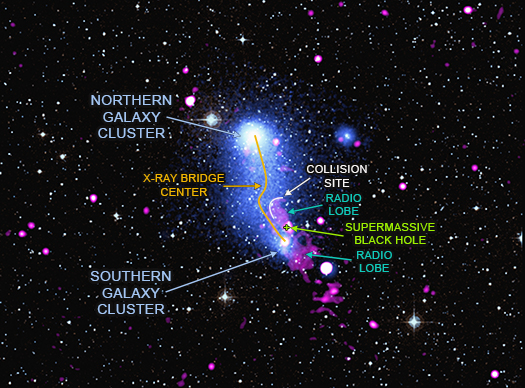

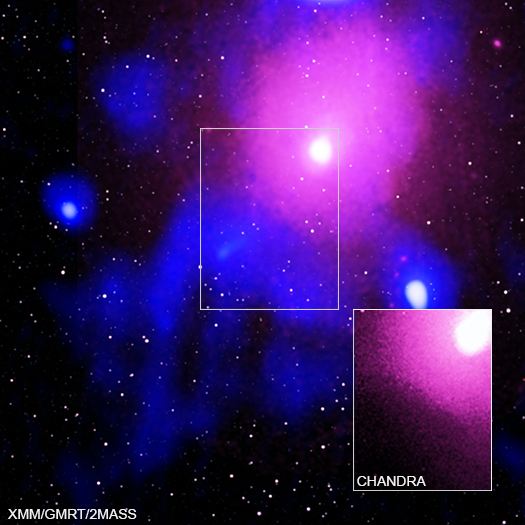

Excavating a Dinosaur in a Galaxy Cluster

Ophiuchus Galaxy Cluster

Credit: X-ray: Chandra: NASA/CXC/NRL/S. Giacintucci, et al., XMM-Newton: ESA/XMM-Newton;

Radio: NCRA/TIFR/GMRT; Infrared: 2MASS/UMass/IPAC-Caltech/NASA/NSF

We are pleased to welcome two guest bloggers, Maxim Markevitch and Simona Giacintucci, who led the study described in our latest press release. Markevitch, an expert on galaxy clusters X-ray studies, got his PhD at the Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences. He worked on ASCA X-ray data in Japan, then at the Chandra X-ray Center for the first 10 years of Chandra operations, and is now at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. He received the AAS Rossi Prize. Giacintucci, the lead author of the study, is an expert in radio phenomena in galaxy clusters. She got her PhD at Bologna University. She was a postdoc at the CfA and an Einstein fellow at the University of Maryland, and is now at the Naval Research Lab.

Galaxy clusters are colossal concentrations of dark matter, galaxies, and tenuous, 100-million-degree plasma. This plasma — gas where the electrons have been stripped from their atoms — slowly loses heat by emitting radiation in the form of X-rays. Around the central peaks of many clusters, where matter concentrates, the plasma gets dense enough* to cool quite fast, on a timescale shorter than the cluster's lifetime (a few billion years). The higher the plasma's density, the more X-rays it emits and the faster it cools. As it cools down, it contracts and becomes denser still, and so on, entering a runaway cooling process. Left unchecked, this process should deposit vast quantities of cold gas in the cluster centers.

We know for a fact that the plasma cools down because we do observe those X-rays — but we don't find nearly as much cold gas in the cluster centers as such runaway cooling must deposit. This has been a puzzle for a long while, and the solution the astronomers converged upon is that there must be some source of additional heat in the central regions of clusters — their “cores” — that doesn't let the plasma cool below 10 million degrees or so.

Early Chandra X-ray images of galaxy clusters pointed to the likely source: the supermassive black holes (SMBH) that sit in the centers of the cluster central galaxies, pull in the surrounding matter, and eject a tiny part of it (just before it sinks irretrievably into the black hole) at nearly the speed of light back into the surrounding gas. Where those jets hit the gas, they blow huge bubbles in it, stir it, generate shocks like sonic booms, etc. (all of these features have been seen in the Chandra images of the cluster cores). The current wisdom holds that these processes together supply the needed heat to prevent runaway cooling from occurring, but at the same time are not so powerful that they blow up the whole plasma cloud, implying some kind of a gentle, self-regulated feedback loop may be occurring.

Galaxy Gathering Brings Warmth

NGC 6338

Credit: X-ray: Chandra: NASA/CXC/SAO/E. O'Sullivan; XMM: ESA/XMM/E. O'Sullivan; Optical: SDSS

As the holiday season approaches, people in the northern hemisphere will gather indoors to stay warm. In keeping with the season, astronomers have studied two groups of galaxies that are rushing together and producing their own warmth.

The majority of galaxies do not exist in isolation. Rather, they are bound to other galaxies through gravity either in relatively small numbers known as "galaxy groups," or much larger concentrations called "galaxy clusters" consisting of hundreds or thousands of galaxies. Sometimes, these collections of galaxies are drawn toward one another by gravity and eventually merge.

Using NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, ESA's XMM-Newton, the Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope (GMRT), and optical observations with the Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico, a team of astronomers has found that two galaxy groups are smashing into each other at a remarkable speed of about 4 million miles per hour. This could be the most violent collision yet seen between two galaxy groups.

A Friendly Neighborhood Supermassive Black Hole

Roberto Gilli

We are very happy to welcome Roberto Gilli as our guest blogger. Dr. Gilli is the first author of a paper that is the subject of our latest Chandra press release. He received his Ph.D. in astronomy from Firenze University in Italy in 2001. Afterward, he did a post-doctoral fellowship at The Johns Hopkins Observatory before returning to Firenze at the Arcetri Astrophysical Observatory. Today, he is an astronomer at the National Institute of Astrophysics (INAF) in Bologna, Italy, a position he has held since 2005. His research interests include active galactic nuclei, quasars, and deep X-ray surveys.

Black holes are usually perceived as dangerous, disruptive systems. On the one hand they swallow copious amount of matter. On the other, they release a large amount of energy in the form of both radiation and matter when enormous quantities of material fall onto them.

The most extreme manifestation of such phenomenon is known as a "quasar" or an "active galactic nucleus" (AGN) that are powered by growing supermassive black holes (SMBHs) at galaxy centers. During these growth phases, part of the gravitational energy of the infalling gas is converted into strong electromagnetic radiation. Meanwhile, some of the gas, rather than being swallowed by the black hole, is instead accelerated and pushed very far away in the form of fast winds or even faster jets that can approach the speed of light.

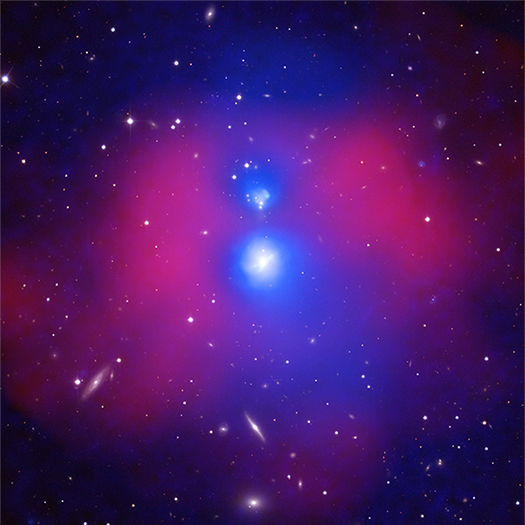

A Weakened Black Hole Allows Its Galaxy to Awaken

The Phoenix galaxy cluster contains the first confirmed supermassive black hole that is unable to prevent large numbers of stars from forming in the core of the galaxy cluster where it resides. This result, reported in our latest press release, was made by combining data from NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and Hubble Space Telescope, and the NSF's Karl Jansky Very Large Array (VLA). A new composite image shows data from each telescope. X-rays from Chandra depict hot gas in purple and radio emission from the VLA features jets in red. Optical light data from Hubble show galaxies (in yellow), and filaments of cooler gas where stars are forming (in light blue).

Witnessing the Formation of One of the Most Massive Objects in the Universe

Gerrit Schellenberger

We welcome Gerrit Schellenberger as our guest blogger. He received his PhD in Bonn, Germany in 2016, and has been a post-doctoral researcher at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian since March 2016. His research includes working on galaxy clusters and groups in large samples for cosmology, but also on individual objects in the X-rays and in the radio regime.

From the beginning of my astronomical career, I was fascinated by studying galaxy clusters, consisting of hundreds, sometimes even thousands of galaxies held together by gravity only. Yet, the galaxies alone do not — by far — sum up to the mass necessary to keep the cluster bound together. Beginning in the 1970s after the birth of X-ray astronomy and the first imaging satellites such as Einstein and ROSAT, scientists discovered that a very hot gas exists between the galaxies of the cluster. The mass of this gas exceeds the mass of all the stars in the galaxies together.

Although this gas is the most dominant, visible structure in galaxy clusters, it is only about 10% of the total mass (while the stars in the galaxies make only about 1%). The rest, roughly 90%, is dark matter, which cannot be observed directly. However, we can see its effect on the hot gas and galaxies in galaxy clusters: the gravity not only keeps the galaxies within the cluster, but also compresses the gas, heating it to the point where it emits X-rays. So we can study dark matter in clusters by measuring the properties (like temperature) of the hot gas from the X-ray emission.

Intrigued by this, I started to analyze a sample comprising 64 clusters during my PhD in Bonn, Germany, with the goal of obtaining total masses (including the dark matter component) for all of them. It turns out that smaller and lighter galaxy clusters, also called galaxy groups, do not follow the expected scaling between X-ray emission and temperature at a given cluster mass, meaning that the X-ray properties of gas in these systems cannot be used to give reliable mass estimates. Therefore, galaxy groups can only be of limited use for cosmological studies, where it is crucial to estimate the amount of matter in objects and how it changes with cosmic time.

Galaxy Clusters Caught in a First Kiss

Cluster Merger

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/RIKEN/L. Gu et al; Radio: NCRA/TIFR/GMRT; Optical: SDSS

For the first time, astronomers have found two giant clusters of galaxies that are just about to collide, as reported in a new press release by RIKEN. This observation is important in understanding the formation of structure in the Universe, sincelarge-scale structures—such as galaxies and clusters of galaxies—are thought to grow by collisions and mergers.

The composite image shows the separate galaxy clusters 1E2215 and 1E2216, located about 1.2 billion light years from Earth, captured as they enter a critical phase of merging. Chandra’s X-ray data (blue) have been combined with a radio image from the Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope in India (red). These images were then overlaid on an optical image from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey that shows galaxies and stars in the field of view.

Does the Gas in Galaxy Clusters Flow Like Honey?

Coma Cluster

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/Univ. of Chicago, I. Zhuravleva et al, Optical: SDSS

This image represents a deep dataset of the Coma galaxy cluster obtained by NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory. Researchers have used these data to study how the hot gas in the cluster behaves, as reported in our press release. One intriguing and important aspect to study is how much viscosity, or "stickiness," the hot gas demonstrates in these cosmic giants.

Galaxy clusters are comprised of individual galaxies, hot gas, and dark matter. The hot gas in Coma glows in X-ray light observed by Chandra. Seen as the purple and pink colors in this new composite image, the hot gas contains about six times more mass than all of the combined galaxies in the cluster. The galaxies appear as white in the optical part of the composite image from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. (The unusual shape of the X-ray emission in the lower right is caused by the edges of the Chandra detectors being visible.)