What Makes an Astronomical Image Beautiful?

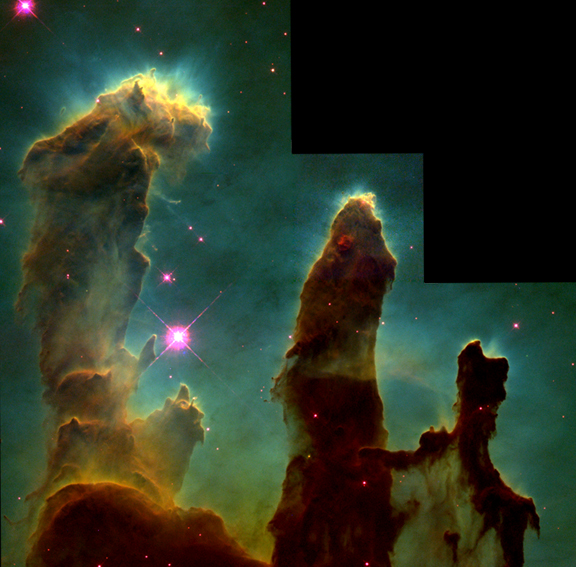

Astronomy is renowned for the beautiful images it produces. It's not hard to be impressed by an image like the Pillars of Creation or the Bullet Cluster, and the more eye-catching an image is, the bigger an audience it can potentially reach. So, as part of our job in astronomy outreach, we have each spent time thinking about what makes an astronomy image beautiful. As professionals, we’d like to go well beyond the intuition of the person who says, "I don't know anything about art, but I know what I like". One approach(1) is to list the key elements that make an image beautiful.

|

|

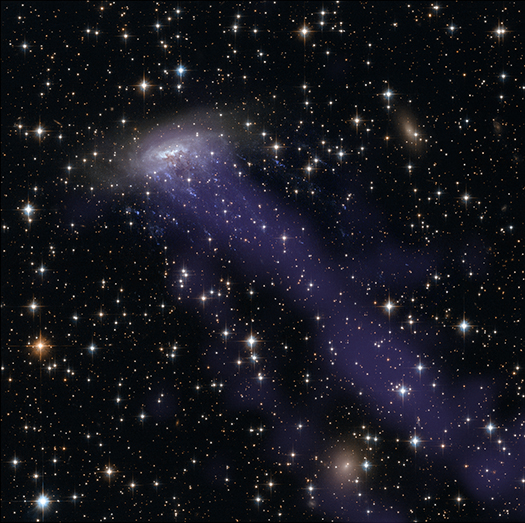

Two famous images, the Pillars of Creation from the Hubble Space Telescope on the left and the Bullet Cluster from the Chandra X-ray Observatory, Hubble and ground-based observatories on the right. Credit: left: NASA, ESA, STScI, J. Hester and P. Scowen (Arizona State University); right: X-ray: NASA/CXC/CfA/M.Markevitch et al.; Optical: NASA/STScI; Magellan/U.Arizona/D.Clowe et al.; Lensing Map: NASA/STScI; ESO WFI; Magellan/U.Arizona/D.Clowe et al.

Celebrating Women History's Month

March is recognized as "Women's History Month" by entities around the country including the federal government. The Chandra X-ray Center is located at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO) in Cambridge, Mass., which has long been tied to the Harvard College Observatory (HCO) in what is known as the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA).

Chandra & XMM-Newton Provide Direct Measurement of Distant Black Hole's Spin

Multiple images of a distant quasar are visible in this combined view from NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and the Hubble Space Telescope. The Chandra data, along with data from ESA's XMM-Newton, were used to directly measure the spin of the supermassive black hole powering this quasar. This is the most distant black hole where such a measurement has been made, as reported in our press release.

Life Is Too Fast, Too Furious for This Runaway Galaxy

The spiral galaxy ESO 137-001 looks like a dandelion caught in a breeze in this new composite image from the Hubble Space Telescope and the Chandra X-ray Observatory.

The galaxy is zooming toward the upper right of this image, in between other galaxies in the Norma cluster located over 200 million light-years away. The road is harsh: intergalactic gas in the Norma cluster is sparse, but so hot at 180 million degrees Fahrenheit that it glows in X-rays detected by Chandra (blue).

Christine Jones Wins Distinguished Smithsonian Honor

We are very proud to announce that the Chandra X-ray Center's Dr. Christine Jones is the recipient of the 2013 Secretary's Distinguished Research Lecture Award from the Smithsonian Institution.

The award recognizes a scholar's sustained achievement in research, long-standing investment in the Smithsonian, outstanding contribution to a field, and ability to communicate research to a non-specialist audience.

Christine has been part of the Chandra family since before "Chandra" even existed. She started her work in the field of X-ray astronomy as an undergraduate at Harvard. With the 1970 launch of Uhuru, the first satellite devoted exclusively to X-ray astronomy, Christine studied Cygnus X-1, a binary X-ray source in which a black hole orbits a normal star.

Runaway Pulsar Firing an Extraordinary Jet

An extraordinary jet trailing behind a runaway pulsar is seen in this composite image that contains data from NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory (purple), radio data from the Australia Compact Telescope Array (green), and optical data from the 2MASS survey (red, green, and blue). The pulsar - a spinning neutron star - and its tail are found in the lower right of this image (mouse over the image for a labeled version). The tail stretches for 37 light years , making it the longest jet ever seen from an object in the Milky Way galaxy, as described in our press release.

Running at Breakneck Speed With Open Arms

Lucia Pavan graduated with a master thesis in astronomy at the University of Padova (the same town from which Galileo discovered Jupiter's moons). Four years later she also got her PhD in Physics at the same university, working on "magnetars" -a particular kind of pulsars, with the highest magnetic fields. After the PhD, she obtained a postdoc position at the University of Geneva - Switzerland, working at the INTEGRAL Science Data Center (ISDC). In between, she moved to the US, working at University of Wisconsin-Madison for a few months. She currently lives in Geneva, working at the ISDC.

When I started to work on the sources discovered by the INTEGRAL satellite, I didn’t expect to find an object that was extraordinary not only for the properties of its emission, but also for its extension and shape in the sky. And yet this was the case when I came across IGR J11014-6103.

INTEGRAL is an ESA satellite in operation since 2002, sensitive mainly to X-ray and gamma-ray bands. The satellite has been accumulating data since the beginning of the mission, providing information on an always-growing number of X-ray emitters. It is thanks to this ability that new objects are continuously discovered. A large fraction of the sources that INTEGRAL has found still lacks any physical classification, a perfect area for new findings to be done.

The Art of Astrophysics

Recently, a group at MIT's Kavli Institute held a contest called "The Art of Astrophysics". Just this week, they announced the winners. Here's an excerpt of an email from the organizers:

A New Look at an Old Friend

Astronomers have used NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and a suite of other telescopes to reveal one of the most powerful black holes known. The black hole has created enormous structures in the hot gas surrounding it and prevented trillions of stars from forming.

Extreme Power of Black Hole Revealed

Astronomers have used NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and a suite of other telescopes to reveal one of the most powerful black holes known. The black hole has created enormous structures in the hot gas surrounding it and prevented trillions of stars from forming.