For Release: March 4, 2025

NASA/CXC

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO/Univ Mexico/S. Estrada-Dorado et al.; Ultraviolet: NASA/JPL; Optical: NASA/ESA/STScI (M. Meixner)/NRAO (T.A. Rector); Infrared: ESO/VISTA/J. Emerson; Image Processing: NASA/CXC/SAO/K. Arcand;

Press Image, Caption, and Videos

After tracking a puzzling X-ray signal from a dying star for decades, astronomers may have finally explained its source: The old star might have destroyed a nearby planet.

Dating back to 1980, X-ray missions have picked up an unusual reading from the center of the Helix Nebula. Using today’s most powerful X-ray missions, NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and ESA’s (European Space Agency’s) XMM-Newton, they now have a much clearer picture of this decades-long enigma.

The Helix Nebula is a so-called planetary nebula, which is the late stage of a star that has ejected its outer layers of gas and left behind a dimmer and smaller ember of a star known as a white dwarf.

In previous decades, the Einstein X-ray Observatory and ROSAT telescopes detected highly energetic X-rays coming from the white dwarf at the center of the Helix Nebula named WD 2226-210, located only 650 light-years from Earth. White dwarfs like WD 2226-210 do not typically give off strong X-rays.

A new study featuring the data from Chandra and XMM-Newton may finally have settled the question of what is causing these X-rays from WD 2226-210.

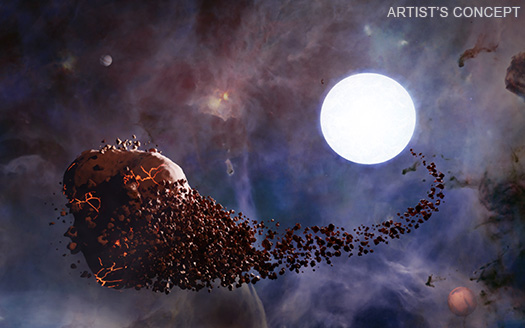

“We think this X-ray signal could be from planetary debris pulled onto the white dwarf, as the death knell from a planet that was destroyed by the white dwarf in the Helix Nebula,” said lead author Sandino Estrada-Dorado of the National Autonomous University of Mexico. “We might have finally found the cause of a mystery that’s lasted over 40 years.”

Credit: NASA/CXC/SAO/M. Weiss

Previously scientists determined that a Neptune-sized planet is in a very close orbit around the white dwarf — completing one revolution in less than 3 days. The researchers in this latest study conclude that there could have been a planet like Jupiter even closer to the star.

The besieged planet could have initially been a considerable distance from the white dwarf but then migrated inwards by interacting with the gravity of other planets in the system. Once it approached close enough to the white dwarf, the gravity of the star would have partially or completely torn the planet apart.

“The mysterious signal we’ve been seeing could be caused by the debris from the shattered planet falling onto the white dwarf’s surface, and being heated to glow in X-rays,” said co-author Martin Guerrero of The Institute of Astrophysics of Andalusia in Spain. “If confirmed, this would be the first case of a planet seen to be destroyed by the central star in a planetary nebula.”

The study shows that the X-ray signal from the white dwarf has remained approximately constant in brightness between 1992, 1999, and 2002 (with observations by ROSAT, Chandra and XMM respectively). The data, however, suggests there may be a subtle, regular change in the X-ray signal every 2.9 hours, providing evidence for the remains of a planet exceptionally close to the white dwarf.

The authors also considered whether a star with a low mass could have been destroyed, rather than a planet. Such stars are about the same size as a Jupiter-like planet but are more massive, making them much less likely to have been torn apart by the white dwarf.

WD 2226-210 has some similarities in X-ray behavior to two other white dwarfs that are not inside planetary nebulas. One is possibly pulling material away from a planet companion, but in a more sedate fashion without the planet being quickly destroyed. The other white dwarf is likely dragging material from the vestiges of a planet onto its surface. These three white dwarfs may constitute a new class of variable, or changing, object.

“It’s important to find more of these systems because they can teach us about the survival or destruction of planets around stars like the Sun as they enter old age,” said co-author Jesús Toala of the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

A paper describing these results appears in The Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society and is available online. NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, manages the Chandra program. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory's Chandra X-ray Center controls science operations from Cambridge, Massachusetts, and flight operations from Burlington, Massachusetts.

Media Contacts:

Megan Watzke

Chandra X-ray Center, Cambridge, Massachusetts

617-496-7998

mwatzke@cfa.harvard.edu

Lane Figuerora

Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, Alabama

256-544-0034

lane.e.figueroa@nasa.gov