For Release: January 08, 2014

CXC

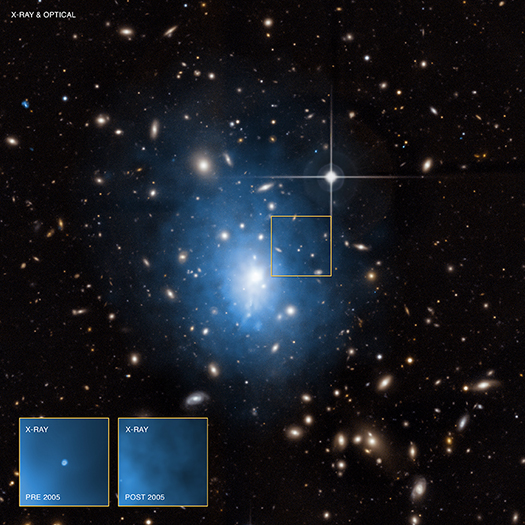

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/Univ. of Alabama/W.P.Maksym et al & NASA/CXC/GSFC/UMD/D.Donato, et al; Optical: CFHT

Press Image and Caption

A bright, long duration flare may be the first recorded event of a black hole destroying a star in a dwarf galaxy. The evidence comes from two independent studies using data from NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and other telescopes.

As part of an ongoing search of Chandra's archival data for events signaling the disruption of stars by massive black holes, astronomers found a prime candidate. Beginning in 1999, an unusually bright X-ray source had appeared in a dwarf galaxy and then faded until it was no longer detected after 2005.

"We can't see the star being torn apart by the black hole," Peter Maksym of the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, AL, who led one of the studies, “but we can track what happens to the star's remains, and compare it with other, similar events. This one fits the profile of 'death by a black hole.'"

Scientists predict that a star that wanders too close to a giant, or supermassive, black hole could be ripped apart by extreme tidal forces. As the stellar debris falls toward the black hole, it would produce intense X-radiation as it is heated to millions of degrees. The X-rays would diminish in a characteristic manner as the hot gas spiraled inward.

In the past few years, Chandra and other astronomical satellites have identified several suspected cases of a supermassive black hole ripping apart a nearby star. This newly discovered episode of cosmic, black-hole-induced violence is different because it has been associated with a much smaller galaxy than these other cases.

The so-called dwarf galaxy is located in the galaxy cluster Abell 1795, about 800 million light years from Earth. It contains about 700 million stars, far less than a typical galaxy like the Milky Way, which has between 200 and 400 billion stars.

Moreover, the black hole in this dwarf galaxy may be only be a few hundred thousand times as massive as the Sun, making it ten times less massive than the Galaxy's supermassive black hole, and placing it in what astronomers call an "intermediate mass black hole" category.

"Scientists have been searching for these intermediate mass black holes for decades," said Davide Donato of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) in Greenbelt, Md., who led a separate team of researchers. "We have lots of evidence for small black holes and very big ones, but these medium-sized ones have been tough to pin down."

The evidence for a star being ripped apart by the dwarf galaxy's black hole came from combing through Chandra data that had been taken over several years. Because Abell 1795 is a target that Chandra observes regularly to help calibrate its instruments, the researchers had access to an unusually large reservoir of data on this object.

"We are very lucky that we had so much data on Abell 1795 over such a long period of time," said Donato's co-author Brad Cenko, also of GSFC. "Without that, we could never have uncovered this special event."

The dwarf galaxy's location in a galaxy cluster also makes it a potential victim of another type of cosmic violence. Because galaxy clusters are crowded with galaxies, it's possible that a large number of stars have been pulled away from the dwarf galaxy by gravitational interactions with another galaxy in the past, a process called tidal stripping.

"It looks like the stars in this galaxy not only need to worry about the black hole in the center," said Makysm's co-author Melville Ulmer of Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill. "They might also be stolen away on the outside by gravity from a passing galaxy."

Astronomers believe that intermediate mass black holes may be the "seeds" that ultimately formed the supermassive black holes in the centers of galaxies like the Milky Way. Finding additional nearby examples should teach us about how these primordial galaxies from the early universe grew and evolved over cosmic time.

Some of the additional clues to this star attack came from NASA's Extreme Ultraviolet Explorer that picked up a very bright ultraviolet source in 1998, which could have marked a time just after the star was initially torn apart. A flare in X-rays may have also been detected with ESA’s XMM-Newton satellite in 2000.

Peter Maksym presented these results today at the 223rd meeting of the American Astronomical Society meeting in Washington, DC on behalf of his team. A paper describing their work is available online and was published in the November 1st, 2013 issue of the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. The paper by Davide Donato and his colleagues on this same event is available online and was accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal.

NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala., manages the Chandra program for NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Mass., controls Chandra's science and flight operations.

For Chandra images, multimedia and related materials, visit:http://www.nasa.gov/chandra

For an additional interactive image, podcast, and video on the finding, visit:

http://chandra.si.edu

Media contacts:

Megan Watzke

Chandra X-ray Center, Cambridge, Mass.

617-496-7998

mwatzke@cfa.harvard.edu

Visitor Comments (9)

I have read that when two black holes collide a medium sized black hole is generated. How is it possible? Due to the huge gravitational pull should it not combine together and form a massive black hole?

Posted by NAVEEN BHARGAV on Friday, 12.19.14 @ 12:36pm

Do you know how far the closest black whole is?

Posted by Brandon Harrison on Saturday, 03.1.14 @ 20:30pm

What if these black holes are nothing than an open gates to others cosmos.

Posted by Khelifa Elagoune on Wednesday, 01.22.14 @ 18:48pm

A natural question arises from these observations could such dwarf galaxy have been bigger or much bigger in the past and its central black hole swallowed nearby gas and stellar dust or even entire solar systems during the time, causing that galaxy to shrink significantly? If affirmative, the next question could be has such process occurred progressively during billions of terrestrial years or a catastrophic event happened at a galactic scale in a very short interval of time in the past and the galaxy shrank very fast?

Posted by Cristian Chidesa on Monday, 01.20.14 @ 18:42pm

You state "Scientists predict that a star that wanders too close to a giant, or supermassive, black hole could be ripped apart by extreme tidal forces." but the tidal force at the event horizon of supermassive black holes is mild. Isn't it more likely that the accretion disk dynamics and the absolute gravity not tidal forces, or differential gravity lead to the radiation signature? See, e.g., Jeremy D. Schnittman, Julian H. Krolik, Scott C. Noble. The Astrophysical Journal, 2013 769/2/156 DOI 10.1088/0004-637X/769/2/156

Posted by brond on Sunday, 01.12.14 @ 14:58pm

Sherri, how do you suppose any information would be transmitted from inside a black hole's event horizon? It's called "black" because the gravitational pull is so great that nothing can get out, not even light.

As for what's on the other side, there isn't another side. Stars that get sucked in are simply ripped apart and compressed, forming part of the black hole's great mass.

Posted by David Harley on Saturday, 01.11.14 @ 22:26pm

The black hole, Sherri, would destroy Chandra before it could get into the innards of the black whole once it past the event horizon. Even if it could the signal could never get out of the black hole.

Marvin L. S.

Posted by Marvin L. S. on Saturday, 01.11.14 @ 17:56pm

I personally believe that it is worth sending Chandra into the black hole considering that we can possibly open man-kind to the mystries of not only black holes, but also theoretical white holes and worm holes. However, considering that black holes come in different shapes or so I was told by my AP Physics teacher, would we not have to make sure that the shape of the black hole corresponds with the typical shape of a worm hole.

Posted by Sagar Patel on Saturday, 01.11.14 @ 09:40am

Could we send Chandra into a black hole so that we can know what goes on inside or on the other side of it? Is that possible? not that I would like to lose Chandra, but it would be extremely educational, don't you agree?

Posted by Sherri on Thursday, 01.9.14 @ 00:14am