A Scientist’s Journey: Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar

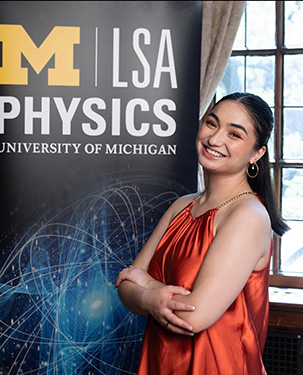

Nicole Kuchta, Communications, Education and Engagement intern at NSF NOIRLab. Photo Credit: NOIRLab

Our guest blogger today is Nicole Kuchta. Nicole Kuchta is a Communications, Education and Engagement intern at NSF NOIRLab. She specializes in astronomy writing and content creation, having also worked with the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and NASA’s Universe of Learning.

Every day our Sun rises in the east and sets in the west, but one day in the (very) distant future things will change. The stars in our universe, including our Sun, live for a finite period, and eventually die.

Right now, in the Sun’s core, hydrogen fuses together to form helium, letting out heat and light. In about 5 billion years, however, the Sun will run out of hydrogen. It will expand to a phase that astronomers call a red giant: a cooler and larger star combining atoms to form heavier and heavier elements. At this stage, the Sun will expand to swallow Mercury, Venus, and then, likely, our Earth.

When the Sun completely runs out of fuel, its glowing outer layers of gas will waft away into a vivid, airy, hot cloud called a planetary nebula. In the core of this ghostly structure will sit the remainder of the once-living Sun: a white dwarf. The Sun at this point will become a ball of carbon under intense pressure and heat, like a ghostly diamond in the sky. It’ll be half the Sun’s original mass packed into a sphere about the size of Earth.

All this might sound like the plot of a sci-fi movie, but it’s anything but fiction. How do we know the future of our Sun? Scientists have studied stars for decades, developing and testing ideas as new data becomes available. This field of study is what astrophysicists call stellar evolution, or the journey of stars’ lives.

The story of Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar — a theoretical astrophysicist who revolutionized what we know about stellar evolution and namesake of the Chandra X-ray Observatory — helps explain how we arrived at our current understanding.

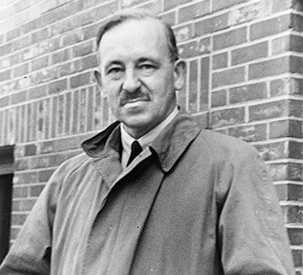

Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar; Photo Credit: AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection

Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar (often referred to by his nickname Chandra) was born in 1910 and grew up in Madras, India, which is known today as Chennai. His family’s house was in a city that was home to prominent lawyers, scholars, authors, and musicians: a place rich with art and learning. His family had the resources to get a good education and the pressure to take it seriously.

His grandfather was a math professor and his uncle, C.V. Raman, won the 1930 Nobel Prize in physics: the first person of color to do so. Chandra’s father worked in the government and taught him subjects like English and math. His father wanted to prepare him for the Indian Civil Service examination so that Chandra could follow a similar career path. Chandra’s mother believed that he would excel the most in doing what he was truly passionate about, which gave him the courage to pursue his growing love for science.

With his mother’s encouragement, Chandra enrolled at Presidency College in Madras to earn his Bachelor of Science in physics. As an undergrad, he worked hard on a research project about how light and matter interact. He knew his results were important. At the time, there was no better place to get your scientific research published than in the Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. However, they only accepted research that was submitted by a “Fellow of the Royal Society” — in other words, someone who was already established in their organization.

Luckily, Chandra found a physicist working on a similar concept, Sir Ralph Fowler, to promote his paper. This publicity (and, of course, his passion for learning) earned him a scholarship from the government of India to go to graduate school in England. A year later, Chandra boarded a steamboat heading to Trinity College at the University of Cambridge. Waiting for him was the man who promoted his research paper, Sir Fowler, who would now be his PhD advisor.

Studying the Sun’s life was one of the avenues of Fowler’s research. We know today that the Sun and stars of similar mass will expand into cooler red giants and then shrink to dead white dwarfs. However, this was not understood back then. In the 1920s, white dwarfs were a new discovery. They could be identified by their extreme density. Out of the hundreds of thousands of cataloged stars at the time, only three were found to be white dwarfs. Today, we’ve identified well over 300,000 of them.

At the time, astrophysicists believed that every star would end its life as a white dwarf. However, they didn’t understand how this fate was even possible. A typical star is in a state of equilibrium. The fusing of elements in a star’s core creates pressure that pushes outward. This pressure balances the force of gravity pulling the star’s gas inward. The dueling forces of pressure and gravity are what make stars spherical. But nothing is being fused inside a white dwarf, so what could be preventing gravity from winning?

Fowler had a unique solution to this issue. He proposed a model of a white dwarf where the atoms in the star’s core are shoved together extremely tightly so that they push against each other in a way that creates outward pressure. This supports the star against the collapse of gravity inward. This is known as electron degeneracy pressure. He published a paper that concluded that all stars, regardless of how massive they are, could exist as white dwarfs because of electron degeneracy pressure.

Yet something was wrong. Nothing can move faster than the speed of light (186,000 miles per second). Einstein proposed that objects moving close to this speed act weirdly because of something called special relativity. In this theory, time can stretch and slow, and an object’s mass can change as it moves at near-light speeds.

In Fowler’s white dwarf model, electrons have to move close to the speed of light to produce electron degeneracy pressure. Chandra, sailing to Cambridge, read this paper and realized that Fowler hadn’t considered special relativity in his math. He modified the paper, adding in the effects of near-light-speed travel, and came to an incredible result. He found that white dwarfs larger than 1.44 times the mass of the Sun are too massive. So massive, in fact, that their gravity is too strong to be counteracted by electron degeneracy pressure. Instead, they collapse.

If high mass stars couldn’t fade away as white dwarfs, then they had to have a different fate. The limit he found is known today as the Chandrasekhar Limit. This was a huge discovery in astronomy; it was also a huge problem for one of the most prominent and influential astrophysicists of the time: Sir Arthur Eddington.

Sir Arthur Eddington; Photo Credit: George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

Eddington was a professor at Cambridge. He ate with Chandra at a table for “distinguished scholars” and would drop by Chandra’s office to chat about his ongoing research. While clever and innovative, Eddington could also be stubborn — especially with his theories on stars.

Chandra’s work disagreed with Eddington’s idea that all stars eventually become white dwarfs. In 1934, Chandra submitted his finished research papers to the Royal Astronomical Society. They raised some major questions, like what would happen if a white dwarf had too much mass? What would a star collapsing look like? And (most importantly), what happens to high-mass stars at the end of their lives?

Chandra didn’t know. In fact, no one knew. Eddington saw this as a weakness. Chandra soon accepted an invitation to present his work in front of the Royal Astronomical Society. He talked confidently about white dwarfs and the mass limit he found. Towards the end of his presentation, he highlighted the most important result of his work: the fate of a low-mass star must be different from that of a high-mass star.

When he finished, Eddington walked up to the front of the room and accused Chandra of rearranging equations without any basis. He went on to challenge Chandra, asking if all stars weren’t going to end up as white dwarfs, what were they going to do? Just disappear?

Before Chandra had a chance to respond, the next speaker was called up. Nobody challenged Eddington’s comments. Eddington then continued to another meeting in Paris, and again called Chandra’s work ‘monstrous’ and the idea of his mass limit ‘absurd’.

Chandra was haunted by this experience. He sent letter after letter to physicists arguing the validity of his work. Despite everything, Chandra dealt with the situation gracefully, even continuing to call Eddington a friend. His time at Cambridge still proved constructive as he compiled the full theory of white dwarfs he worked on into a book.

At the same time, on the other side of the world, Chandra was being considered for a job at Yerkes Observatory in Wisconsin. Yerkes was run by the University of Chicago and housed the world’s largest refracting telescope at the time. This telescope uses a lens 40 inches wide to focus light from the sky and weighs over 80 tons — about double the weight of a humpback whale.

When the president of UChicago offered Chandra a position as an assistant professor, he accepted. As a professor, he was engaging and dedicated. Twice a week, he would drive an hour and a half from Yerkes to UChicago to teach a handful of students. During a blizzard, only two students braved the storm and attended his class. These students, Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen Ning Yang, ended up winning the Nobel Prize in Physics together years later.

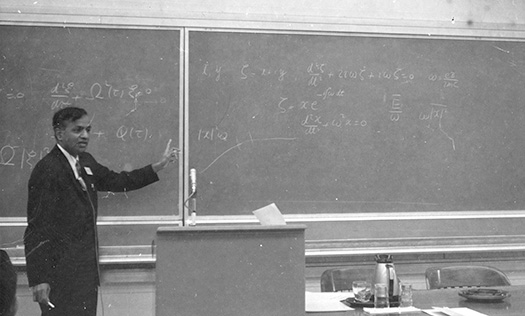

Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar lecturing at a blackboard. Photo Credit: AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection

When he wasn’t teaching, Chandra was busy researching. He developed a unique pattern in his work. He would go through decade-long periods where he’d dive deep into a specific topic, like general relativity or black holes. Then he would publish papers, seeking answers to the problems he found most interesting.

For example, the sky is blue because of an effect known as Rayleigh scattering — a tendency for bluer light to scatter more in the atmosphere than redder light. When the sun is highest in the sky, it has the least atmosphere to travel through, or to scatter its light, making the sky appear bluer. When the sun is low in the sky at sunset, however, it has more atmosphere to travel through horizontally before reaching our eyes. More atmosphere means more scattering of bluer light, making the sunlight appear reddish. This theory was first presented in 1871 but was never proven with actual numbers and calculations until Chandra completed it in 1954 — one of his favorite challenges of his career.

A sunset seen from the International Space Station. Photo Credit: NASA

When he was done with a topic, he’d write a book summarizing the major things he had learned. This pattern led him to write 380 papers and 10 books. His broad physics knowledge brought him many unique opportunities. For example, Robert Oppenheimer invited him to join the Manhattan Project, the secret WWII program that developed the atomic bomb, because of the expertise he developed in hydrodynamics, the study of how fluids move. However, his non-US citizen status at the time prevented him from contributing.

Chandra’s expertise also led him to become the sole editor of The Astrophysical Journal, an astronomy research publication, for 19 years. This was a very important (and stressful) position to hold. He had many responsibilities: reviewing paper submissions, looking for math errors, and solving each edition’s production problems. Under his supervision, the Astrophysical Journal went from having an audience only at UChicago to becoming the leading international publication of astronomy research.

Even with so much of his life devoted to physics, Chandra found time to appreciate all manner of art, such as poetry, plays, music, and paintings. He gave lectures like “Shakespeare, Newton, and Beethoven or Patterns of Creativity,” where he compared the motivation people have to learn science with the motivation to create art.

While Chandra went on exploring different areas of physics and the humanities, astrophysicists elsewhere were slowly catching up to the idea he theorized at age 19: not all stars die as white dwarfs.

With the advent of the atomic bomb in World War II, there was increased interest in studying supernovae: massive stars exploding at the end of their lives. Scientists began leaning into a theory that a stellar remnant called a neutron star could be left behind after a supernova. Neutron stars are essentially balls of neutrons packed together very, very tightly. In fact, neutron stars could have double the mass of the Sun crammed into a sphere about the size of Manhattan, or about 100 million times the density of a white dwarf. Even wilder, supernovae were theorized to alternatively leave behind black holes, regions of space where gravity is so strong, not even light can escape.

In 1966, two scientists in California modeled stars on the verge of exploding using a new technique: computer simulations. They built a computer program that used mathematical models to mimic the behavior of a real system like a supernova. While today our simulations can be done with a sleek laptop, Stirling Colgate and Richard White were using big, boxy machines spitting out long strings of numbers. As they processed the data they generated, they found that inside a dying high mass star, a core can collapse into a neutron star, violently expelling the rest of its material. But, if there is too much mass for a neutron star to be stably formed, they found that the star “collapse[s] indefinitely, to a point of infinite density” — a black hole.

Colgate and White wrote up a paper and submitted it to The Astrophysical Journal, to be reviewed by its editor — Chandra himself. Imagine his excitement at seeing support and evidence for new stellar corpses outside of white dwarfs. He helped edit the paper, adding references to his past work and even Eddington’s.

After theories and simulated data, came observations from the universe. In 1967, Jocelyn Bell, then a graduate student at Cambridge University, detected a strange pulsing from a mysterious source that wasn’t a white dwarf. Then, the year after her discovery, a similar signal was detected from another structure in the sky known as the Crab Nebula. These were some of the first ever confirmed signals from neutron stars. Finally, in 1971, the first evidence of a black hole was identified, further backing Chandra’s theory.

Neutron stars and black holes being proven real validated the ideas that Chandra had at the very beginning of his career. Not all stars die as white dwarfs.

In 1983, at age 73, Chandra won the Nobel Prize for physics. Chandra passed away in 1995, but his discoveries in astrophysics deeply influence today’s research. Four years later, on July 23, 1999, NASA launched the Chandra X-ray Observatory, honoring his name and legacy.

X-rays are waves of light that are invisible to the human eye. They reveal information about the aftermath of supernovae, the behavior of neutron stars, and matter swirling into black holes. In fact, one of Chandra's first images was of a supernova remnant, Cassiopeia A, and the neutron star tucked within.

More than 25 years after it began its mission, NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory continues to make new discoveries about stars and their evolution, continuing the path that Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar started almost a century ago.

—Written by Nicole Kuchta, edited by Rutuparna Das

This article received Federal support from the Asian Pacific American Initiatives Pool, administered by the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center.