Disclaimer: This material is being kept online for historical purposes. Though accurate at the time of publication, it is no longer being updated. The page may contain broken links or outdated information, and parts may not function in current web browsers. Visit chandra.si.edu for current information.

Mirror Man

September 27, 2013 ::

by Harvey Tananbaum and Wallace Tucker

Less than 50 years after the first detection of an extrasolar X-ray source, the Chandra X-ray Observatory has achieved an increase in sensitivity comparable to going from naked-eye observations to the most powerful optical telescopes over the past 400 years. Many individuals have been involved in this phenomenal accomplishment, but in this contribution, we focus on one: Leon Van Speybroeck.

Leon was one of a number of newly minted MIT physics Ph.D.'s (including Paul Gorenstein, Martin Zombeck, Ethan Schreier, and one of us (HT)) who in the mid-late1960's made the short move from the MIT campus to the revamped milk-truck garage a few blocks away that was the site of American Science & Engineering. It was there that Riccardo Giacconi had assembled an X-ray astronomy group that had discovered the first cosmic X-ray source during a short rocket flight.

Having founded a new field of astronomy, Riccardo pressed his advantage with NASA, and proposed a bold program that included more rocket flights, a small satellite dedicated to X-ray observations, and an X-ray telescope. The proposed X-ray telescope would required nested grazing incidence mirrors capable of a few arc seconds resolution, which was a venture into entirely new territory.

Leon joined in this effort with Riccardo, Giuseppe Vaiana, and others. By the time we had arrived (HT in 1968, WT in 1969) at AS&E Leon was in charge of designing the first nested grazing incidence telescope, which subsequently flew on Skylab. This telescope produced stunning, high-resolution X-ray images of the solar corona.

These images demonstrated that the X-ray emission from the solar corona is highly structured, and that magnetic fields played an important role in heating the solar corona. The images also served another purpose: they demonstrated the feasibility of a high-resolution X-ray telescope for extrasolar X-ray astronomy.

"The Skylab images made a tremendous impression," recalled Al Schardt, who was chief of NASA's Astrophysics Division at the time. "It was clear that an X-ray telescope could work. Before that we had never been sure."

By the time the Skylab images starting coming in, and before Leon could enjoy the scientific fruits of working on the interpretation of the images, he was deep into the next project: designing mirrors for an X-ray telescope for much fainter, extra-solar sources. This telescope would become the Einstein X-ray Observatory. It was during this period that Leon would establish himself as the world's premier X-ray mirror designer and builder.

As the telescope scientist, Leon's job was not merely to design the best X-ray mirrors ever made. He had to do it for the lowest possible cost, and under the pressure of a rigid schedule dictated by budget pressures. One of us (HT) was assigned by Riccardo to help Leon with interfaces to program managers and project engineers responsible for costs and budgets. Leon "detested" putting aside the technical work to write a progress report or attend a planning meeting. An "offer" (by HT) to write the report or represent the team solo at a meeting was often sufficient to get Leon's attention and his needed assistance with the programmatic efforts.

Leon used computer ray-tracing and lab experiments to test the design. The mirrors were always on his mind and often in his meticulous, demanding sight.

In Riccardo's words, "Leon hovered over those mirrors like a mother hen."

Indeed, he literally slept with them, never letting them out of his sight during the crucial periods.

At Perkin-Elmer, with Peter Young's cooperation, Leon pushed for ever more precise polishing of the mirrors and better testing procedures at every step of the process, pressing the limits of existing technology and at times trying NASA's patience. At more than one stage NASA intervened at what Leon and the mirror team considered arbitrary schedule milestones to force them to move on beyond what NASA considered excessive striving for perfection, although in his defense it is fair to state that Leon was simply endeavoring to meet the established requirements and not cut short the efforts due to fiscal or schedule pressures.

Leon's reaction: "If I were doing it over, I would want to control certain "environments even better."

Leon's oversight prevented countless small mistakes and several large ones. One of the more dramatic examples occurred during the loading of the mirrors. The crate containing the mirror assembly was loaded by a crane onto a truck. The ever cautious Leon insisted that the loading process be tested in a dry run, with a crate containing ballast. On the first run, the crane dropped the crate!

Thanks in no small part to Leon's dedication and incomparable skill in designing the mirrors, Einstein was an immediate success. Albert Opp, then astrophysics science chief at NASA, who had to deal with the budgetary and schedule problems created by what he characterized as "an exceedingly sophisticated, exceedingly complicated undertaking," recalled with some relief that "The X-ray images from HEAO-2 (a.k.a. Einstein) created a tremendous impact on the scientific community. They will go down as milestones in the history of astronomy."

By the time Einstein was launched, plans were already underway to go well beyond that milestone, and build an X-ray telescope that could make sub-arc second images of a quality comparable to the best optical telescopes. To this end, Riccardo and one of us (HT), had submitted a proposal to NASA for what would eventually – meaning 23 years later -- become the Chandra X-ray Observatory.

Once again the X-ray mirrors would be the heart of the observatory, and the heart of the problem in getting the program through NASA. Leon, clear-eyed and honest as always, was the first to acknowledge the latter challenge.

"NASA reviewers were concerned with scale-up issues," he recalled. "And they were right to be concerned. It was going to be difficult."

The rest of the Chandra team, at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO), Marshall Space Flight Center, Northrop-Grumman, Hughes Danbury Optical Systems (nee Perkin-Elmer) and Eastman Kodak agreed with Leon that the task ahead was daunting. But the underlying attitude was typified by a comment that Dan Schwartz, who had worked with Leon on Einstein and was now part of the group assembled to work on Chandra.

"We were always extremely confident we could do the mirrors well," he recalled, "If they would only listen to Leon."

Dan's confidence was not misplaced.

At first light for Chandra, a group of us were gathered in a small room around a monitor, awaiting first light. Leon walked in, and said he wanted to see if Chandra was flying around with a "bucket of broken glass," or a real mirror.

When the first image came into view, it was smeared out by a few arc seconds.

"How big should it be, Leon?" an anxious scientist asked.

"How far off axis are we (i.e., is the source)?" he asked.

"About 5 arc minutes."

"Then a point source should have a size of about 3 arc seconds," he said with a broad grin. "We've got good mirrors."

Leon was still smiling when we left the room about an hour later.

"It's a good start," he acknowledged. "Not a bad start at all."

Riccardo made an excellent assessment of Leon's impact on astronomy in his memoir:

"Leon was one of the most talented physicists I have ever met. He was the scientist who brought to the design of x-ray telescopes a deep understanding of the surface physics, optics, mission requirements and fabrication techniques. He led the effort on the construction of the Skylab telescope and at Perkin-Elmer on the construction of the Einstein and Chandra telescopes, achieving x-ray optics of unparalleled quality. It is clear that much of the scientific success of those missions would not have been possible without his contributions."

In recognition of his contributions to X-ray optics, Leon was awarded the 2002 Bruno Rossi Prize of the High Energy Astrophysics Division of the American Astronomical Society. On learning of this honor, he commented, with characteristic modesty, that "Many, many other people made essential contributions to the Chandra program, and hopefully some of them will receive proper recognition. I am thoroughly enjoying my days in the sun, but am quite humbled by the list of past recipients."

Leon's own description of his work revealed some aspects about his approach to his craft that most of his colleagues already knew, and some that only his friends were aware of.

"I personally would rather try for 99% and get 80% than try for 60% and get 55%. I try to work as closely with individuals as I can. I try very hard to encourage them, and have a great deal of pride in their work. I try to encourage them that this is something that is important, something that will be appreciated by the world."

One of our favorite memories of Leon is the wonder and elation he would express when he viewed early Chandra images. Although he had labored heroically for years in the face of formidable technical challenges and never wavered in his conviction that an X-ray telescope could be built to produce high-resolution images, he beamed with excitement every time he saw the fruits of his efforts, and once described his first look at the images as "almost like a religious experience."

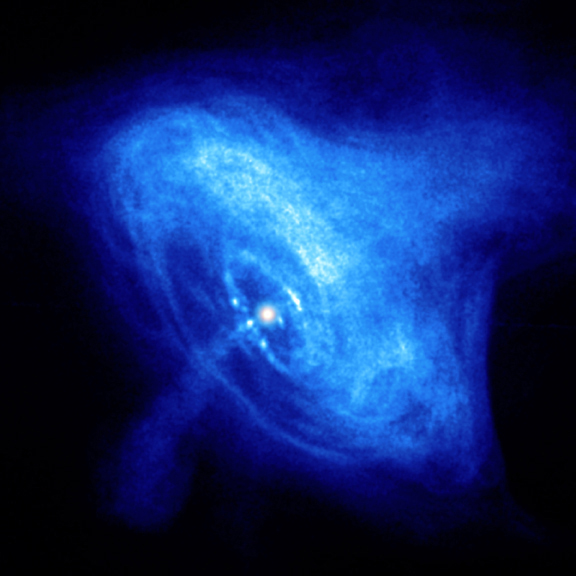

Perhaps because he had thought about and lived with the excruciating demands of building Chandra's mirrors, he seemed more enthralled than others with the images they produce. He would stop by WT's office often to have a look at the latest Chandra image that was being prepared for the press and Chandra web site. One day, the image on the monitor was of the Crab Nebula. Leon, a man who loved science and the precision of equations, and who would tell you he had little use for philosophy and poetry, took in the wonder of the elegantly organized, awesomely powerful, pulsar dynamo revealed by the Chandra image.

After a few moments of silence, he said, in a soft, uncharacteristically reverent tone, "That's a beautiful sight."

Bibliographical Notes

The quotes in this article are from the references given below:

A. Schardt's quote is from Tucker & Giacconi (1985, p. 109)

R. Giacconi's quote on Leon sleeping with mirrors is from Tucker & Tucker (1986, p.83)

Leon's quote on wanting to polish Einstein mirrors more is from Tucker & Tucker (1986, p.83)

Al Opp's quote is from Tucker & Tucker (1986, p. 90)

Leon's quotes on Chandra mirror challenge and his reaction to the Crab image are from Tucker & Tucker 2001, (p.91 and p. 234).

D. Schwartz's quote from Tucker & Tucker (2001, p. 90)

R. Giacconi's assessment of the impact of LVS on X-ray astronomy is from Giacconi (2008).

Leon's quote on his approach to research is from Tucker (1999)

Leon's comment on receipt of Rossi prize is from CXC, (2002)

CXC 2002, CXC PR: 02-01, http://chandra.harvard.edu/press/02_releases/press_012302.html

Chandra Telescope Designer Wins 2002 Rossi Prize

R. Giacconi, 2008, Secrets of the Hoary Deep (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins U. Press)

W. Tucker, 1999, Interview with Leon Van Speybroeck

W. Tucker and R. Giacconi, 1985, The X-ray Universe (Cambridge: Harvard U. Press)

W. Tucker and K. Tucker, 1986, The Cosmic Inquirers (Cambridge: Harvard U. Press)

W. Tucker and K. Tucker, 2001, Revealing the Universe (Cambridge: Harvard U. Press)

Disclaimer: This material is being kept online for historical purposes. Though accurate at the time of publication, it is no longer being updated. The page may contain broken links or outdated information, and parts may not function in current web browsers. Visit chandra.si.edu for current information.