For Release: March 21, 2024

NASA/CXC

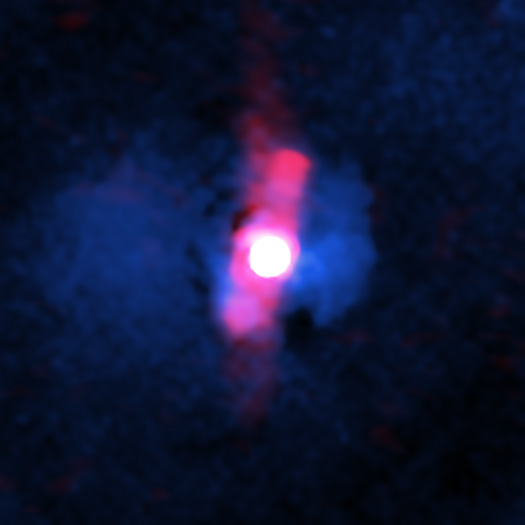

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/Univ. of Nottingham/H. Russell et al.; Radio: NSF/NRAO/VLA; Image Processing: NASA/CXC/SAO/N. Wolk

Press Image, Caption, and Videos

Astronomers have revealed that a brilliant supermassive black hole is not living up to expectations. Although it is responsible for high levels of radiation and powerful jets, this giant black hole is not as influential as many of its counterparts in other galaxies.

A new study using NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory looked at the closest quasar to Earth that is in a cluster of galaxies. Quasars are a rare and extreme class of supermassive black holes that are furiously pulling material inwards, producing intense radiation and sometimes powerful jets. Known as H1821+643, this newly studied quasar is about 3.4 billion light-years from Earth and contains a black hole weighing about four billion times that of the Sun.

Most growing supermassive black holes pull material in less quickly than those in quasars. Astronomers have studied the impact of these more common black holes by observing ones in the centers of galaxy clusters. Regular outbursts from such black holes prevent the huge amounts of superheated gas they are embedded in from cooling down, which limits how many stars form in their host galaxies and how much fuel gets funneled toward the black hole.

Much less is known about how much influence quasars in galaxy clusters have on their surroundings.

“We have found that the quasar in our study appears to have relinquished much of the control imposed by more slowly growing black holes,” said Helen Russell of the University of Nottingham in the United Kingdom, who led the new study. “The black hole’s appetite is not matched by its influence.”

To reach this conclusion the team used Chandra to study the hot gas that H1821+643 and its host galaxy are shrouded in. The bright X-rays from the quasar, however, made it difficult to study the weaker X-rays from the hot gas.

“We had to carefully remove the X-ray glare to reveal what the black hole’s influence is,” said co-author Paul Nulsen of the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian. “We could then see that it’s actually having little effect on its surroundings.”

Using Chandra, the team found that the density of gas near the black hole in the center of the galaxy is much higher, and the gas temperatures much lower, than in regions farther away. Scientists expect the hot gas to behave like this when there is little or no energy input (which would typically come from outbursts from a black hole) to prevent the hot gas from cooling down and flowing toward the center of the cluster.

“The giant black hole is generating a lot less heat than most of the others in the centers of galaxy clusters,” said co-author Lucy Clews of the Open University in the UK. “This allows the hot gas to rapidly cool down and form new stars, and also act as a fuel source for the black hole.”

The researchers determined that hot gas — equivalent to about 3,000 times the mass of the Sun per year — is cooling to the point that it is no longer visible in X-rays. This rapid cooling can easily supply enough material for the 120 solar masses of new stars observed to form in the host galaxy every year, and the 40 solar masses consumed by the black hole each year.

The team also examined the possibility that the radiation from the quasar is directly causing the cluster’s hot gas to cool down. This involves photons of light from the quasar colliding with electrons in the hot gas, causing the photons to become more energetic and the electrons to lose energy and cool down. The team’s study showed that this type of cooling is probably occurring in the cluster containing H1821+643 but is much too weak to explain the large amount of gas cooling seen.

“While this black hole may be underachieving by not pumping heat into its environment, the current state of affairs will likely not last forever,” said co-author Thomas Braben of the University of Nottingham. “Eventually the rapid fuel intake by the black hole should increase the power of its jets and strongly heat the gas. The growth of the black hole and its galaxy should then drastically slow down.”

A paper describing these results appears in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society and is also available online.

NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center manages the Chandra program. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory's Chandra X-ray Center controls science from Cambridge Massachusetts and flight operations from Burlington, Massachusetts.

Media Contact:

Megan Watzke

Chandra X-ray Center, Cambridge, Massachusetts

617-496-7998

mwatzke@cfa.harvard.edu

Jonathan Deal

Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, Alabama

256-544-0034

jonathan.e.deal@nasa.gov